St. Andrew Community Refuge Plan

A community-centered approach to preparedness and stewardship.

1. Executive Summary

1.1 What This Document Is

This document provides a technical and operational analysis for religious institutions considering community refuge operations during hurricane events. Prepared by North Star Group as a systems integration framework, this analysis examines the intersection of structural engineering, emergency management protocols, operational logistics, and financial feasibility for church-based hurricane shelters.

The document synthesizes applicable building codes, FEMA guidance documents, emergency management best practices, and operational protocols to provide decision-makers with technically sound information. While engineering calculations and structural certifications must be performed by licensed professionals, this analysis provides the technical framework necessary for informed decision-making and professional coordination.

This resource addresses the growing interest among religious institutions in formal emergency shelter designation while providing realistic assessments of operational requirements, legal considerations, and financial implications. The analysis is structured to support both internal organizational planning and coordination with county emergency management agencies.

1.2 Why Churches Consider Refuge Operations

Religious institutions naturally serve as community gathering points during crisis events, with many congregants and community members instinctively viewing church facilities as places of stability and safety. This informal role creates both opportunities and responsibilities that organizations may choose to formalize through structured emergency shelter programs.

County emergency management agencies increasingly survey community facilities for potential shelter capacity as part of comprehensive disaster preparedness planning. According to FEMA's Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) guidelines, distributed shelter capacity reduces strain on centralized facilities and provides more accessible options for community members with transportation limitations or special needs.

The National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters (NVOAD) estimates that faith-based organizations provide approximately 80% of post-disaster recovery services, yet many lack formal integration with pre-disaster shelter planning. This represents both an opportunity for enhanced community resilience and a potential gap in emergency response coordination.

Recent hurricane events have demonstrated that informal shelter arrangements often emerge spontaneously during crisis periods. Formalizing these arrangements through proper planning, verification, and resource allocation can significantly improve outcomes for both shelter operators and those seeking refuge.

1.3 Operational Definition of "Refuge"

For the purposes of this analysis, "refuge" refers to time-limited emergency shelter operations providing basic life safety and support services during hurricane events. This differs significantly from both routine building occupancy and full-scale emergency shelters operated by governmental agencies.

Community refuge operations typically provide:

- Structural protection from wind and debris during hurricane passage

- Basic life support services including potable water, sanitation, and lighting

- Climate-controlled environment for extended occupancy periods

- Communication capabilities for emergency coordination and family contact

- Basic food service or food preparation capabilities

- Supervised environment with volunteer staff and basic security

The operational timeframe typically ranges from 24 to 72 hours, beginning before tropical storm-force winds arrive and continuing through initial post-storm assessment periods. This duration reflects the typical pattern of hurricane approach, passage, and immediate aftermath in Gulf Coast communities.

Refuge operations are distinguished from certified storm shelters by their focus on hurricane protection rather than tornado resistance. While both serve protective functions, the engineering requirements, operational protocols, and certification processes differ significantly. FEMA Publication 361, "Safe Rooms for Tornadoes and Hurricanes," provides detailed specifications for both types of facilities.

1.4 Key Organizational Decisions

Religious institutions considering refuge operations must address several fundamental questions that determine operational scope, resource requirements, and coordination obligations:

Population Scope: Organizations must define their target population, ranging from member-only arrangements to broader community access. This decision affects capacity planning, resource allocation, and coordination with county emergency management. The American Red Cross Shelter Operations Manual provides guidance on population assessment and intake procedures for different operational models.

Operational Duration: Refuge operations may be designed for short-term (24-36 hours), moderate-term (48-60 hours), or extended-term (72+ hours) events. Duration directly affects supply requirements, volunteer staffing needs, and infrastructure demands. FEMA's Mass Care Services guidance provides planning factors for different operational timeframes.

Responsibility Scope: Organizations must define their care obligations and operational boundaries. This includes decisions about medical support capabilities, pet accommodation policies, and specialized needs populations. The National Incident Management System (NIMS) provides frameworks for capability assessment and resource coordination.

Facility Modifications: Most existing religious facilities require some level of verification or modification for formal refuge designation. The International Building Code (IBC) provides baseline requirements for assembly occupancy, while ASCE 7 establishes wind load requirements for different risk categories.

Financial Commitment: Refuge operations involve both initial setup costs and ongoing operational expenses. Various federal, state, and local funding programs may offset these costs, but organizations must plan for financial sustainability independent of grant funding.

1.5 Technical and Operational Assessment

Modern religious facilities constructed under recent building codes generally provide a strong foundation for refuge operations, though formal verification and targeted improvements are typically required. Buildings constructed to International Building Code (IBC) 2012 or later incorporate enhanced wind resistance provisions and improved structural connectivity requirements compared to earlier code cycles.

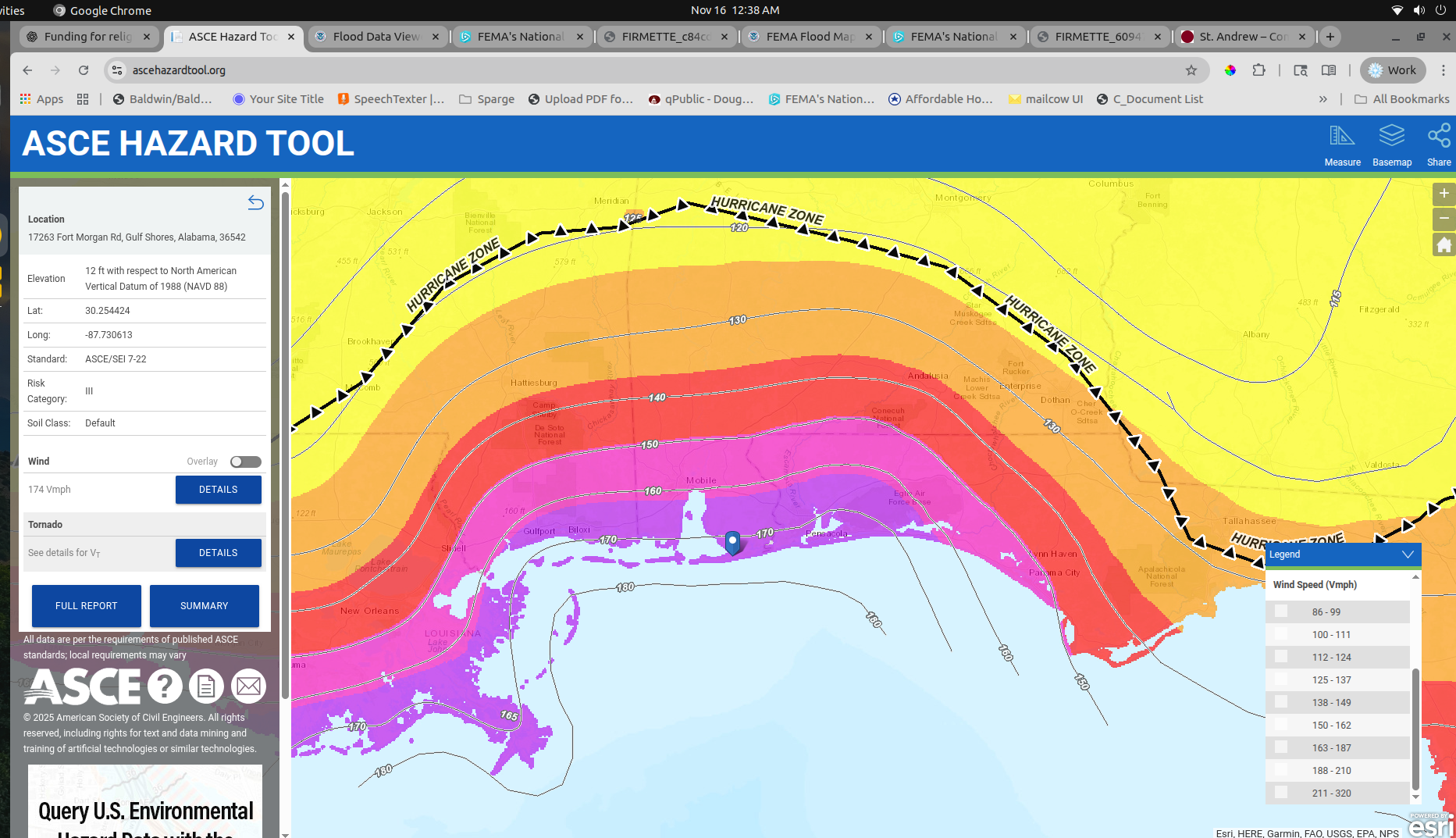

Structural Considerations: Hurricane refuge operations primarily require verification of continuous load paths, roof-to-wall connections, and opening protection. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Standard 7 provides wind load calculation methodologies, while FEMA P-55 addresses coastal construction requirements. Most structural modifications for refuge conversion involve connection reinforcement rather than major rebuilding projects.

Operational Complexity: Successful refuge operations require coordination across multiple functional areas including registration, logistics, food service, sanitation, medical support, pet accommodation, and volunteer management. The American Red Cross publishes comprehensive shelter management protocols that provide operational frameworks adaptable to smaller community-based facilities.

Regulatory Coordination: Formal refuge designation typically requires coordination with local emergency management agencies, building code officials, and fire departments. The Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP) standards provide frameworks for capability assessment and documentation requirements.

Resource Requirements: Basic refuge operations require emergency power, water storage, sanitation supplies, communication equipment, and basic medical supplies. The Federal Emergency Management Agency publishes supply and equipment guidelines for different facility types and operational durations in FEMA Publication 476, "Floodplain Management Requirements."

Funding Opportunities: Multiple federal, state, and local programs provide funding for refuge-related improvements, including FEMA Hazard Mitigation Assistance programs, USDA Community Facilities programs, and state emergency management grants. However, funding is competitive and not guaranteed, requiring organizations to plan for alternative financing approaches.

References

American Red Cross. (2023). Shelter Operations Manual. Washington, DC: American Red Cross National Headquarters. Retrieved from https://www.redcross.org/get-help/disaster-relief-and-recovery-services/find-an-open-shelter

American Society of Civil Engineers. (2022). ASCE 7-22: Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures. Reston, VA: ASCE Press. Retrieved from https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/asce-7

Emergency Management Accreditation Program. (2023). EMAP Standards. Lexington, KY: EMAP Secretariat. Retrieved from https://www.emap.org/standards

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2021). FEMA P-361: Safe Rooms for Tornadoes and Hurricanes. Washington, DC: FEMA. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_safe-rooms-for-tornadoes-and-hurricanes_p-361.pdf

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2019). Mass Care Services. Washington, DC: FEMA. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/practitioners/mass-care

International Code Council. (2021). International Building Code. Country Club Hills, IL: International Code Council. Retrieved from https://www.iccsafe.org/products-and-services/i-codes/2021-i-codes/ibc/

National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters. (2023). NVOAD Member Services. Alexandria, VA: NVOAD. Retrieved from https://www.nvoad.org/member-services/

2. Understanding St. Andrew's Facility

2.1 Overview of the Campus

The St. Andrew By-The-Sea campus consists of three primary structures configured for worship, education, and fellowship activities. The facility layout, construction characteristics, and mechanical systems directly influence refuge capacity calculations, operational flow patterns, and structural verification requirements under hurricane loading conditions.

Campus circulation patterns affect emergency ingress, egress, and internal movement during extended occupancy periods. The International Building Code (IBC) Section 1006 establishes minimum egress requirements for assembly occupancies, while NFPA 101 Life Safety Code provides additional guidance for emergency evacuation and area of refuge designations.

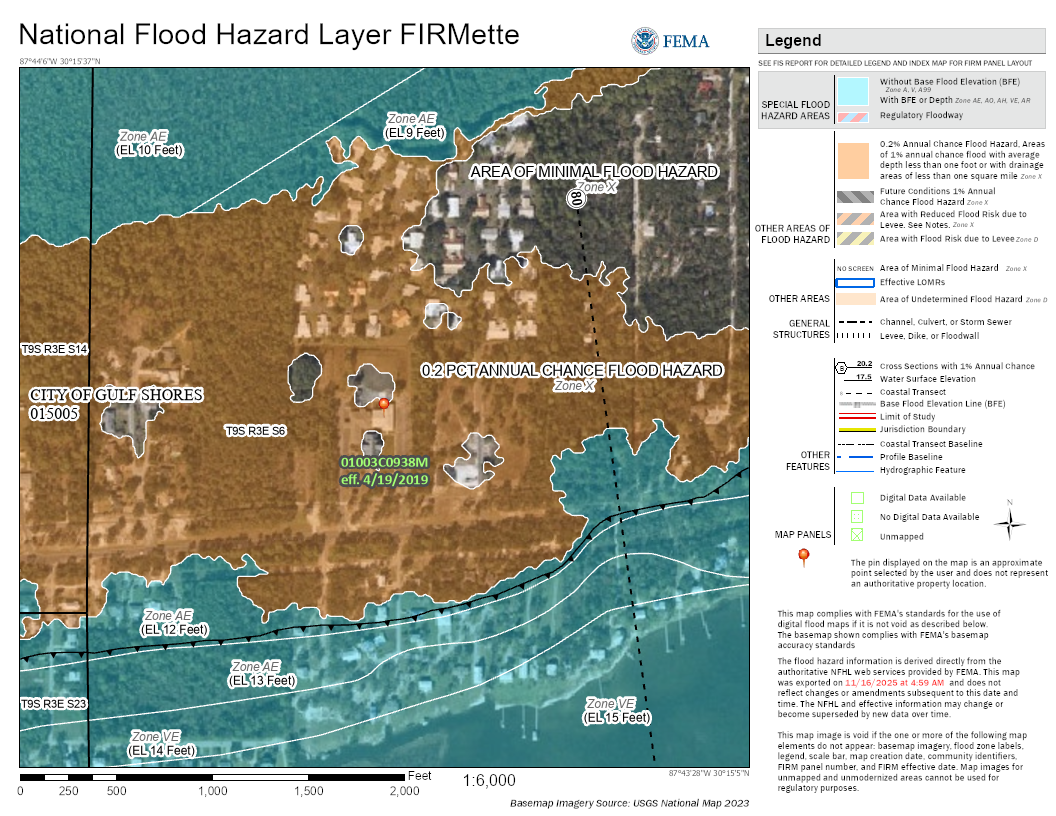

Site topography, drainage patterns, and proximity to flood-prone areas influence facility suitability for refuge operations. FEMA flood maps and local drainage studies provide essential data for assessing flood risk during hurricane events when storm surge and inland flooding commonly occur simultaneously.

2.2 What Buildings Exist Today

2.2.1 Sanctuary

The sanctuary represents a large-volume assembly space with minimal interior structural support elements, creating specific wind load distribution patterns and structural behavior characteristics. Such configurations are classified as "low-rise buildings" under ASCE 7-22 wind load provisions, with specific pressure coefficient applications for large roof areas.

High-volume spaces experience different internal pressure dynamics compared to compartmentalized areas when exterior envelope failures occur. ASCE 7-22 Section 26.13 provides internal pressure coefficient calculations for buildings with varying opening configurations and sizes.

Potential refuge applications include pre-storm assembly areas, community meeting spaces during extended events, and overflow sleeping capacity. However, large-span roof structures require specific engineering verification for refuge occupancy loads, particularly during peak wind events when additional structural stresses occur.

2.2.2 Fellowship/Education Building

Multi-room educational facilities provide optimal configurations for refuge operations due to compartmentalized layouts, distributed mechanical systems, and flexible space allocation capabilities. These characteristics align with American Red Cross shelter management protocols emphasizing privacy, noise control, and functional separation.

Kitchen facilities enable food service operations ranging from simple reheating to full meal preparation. NSF International provides commercial kitchen equipment standards, while local health departments establish operational requirements for temporary food service in emergency shelters.

Classroom spaces accommodate family units, special needs populations, and functional activities including registration, medical triage, and volunteer coordination. The Federal Emergency Management Agency recommends 20-40 square feet per person for sleeping areas, with additional space allocations for circulation, storage, and support functions.

2.2.3 Offices, Hallways, Auxiliary Spaces

Support spaces house critical building systems including electrical panels, communication equipment, mechanical rooms, and emergency supply storage. During refuge operations, these areas require controlled access to maintain operational security and prevent unauthorized system modifications.

Interior corridors without exterior openings often provide the safest refuge areas during peak wind conditions. FEMA P-361 identifies interior rooms, corridors, and closets on the lowest floor as preferred safe areas in buildings not specifically designed as storm shelters.

Mechanical and electrical rooms require access for maintenance and system monitoring during extended operations. The National Electrical Code (NEC) Article 110 establishes working space requirements around electrical equipment that must be maintained during refuge operations.

2.3 How the Buildings Were Built (2010 / 2018 remodel)

Construction under International Building Code (IBC) 2009/2012 cycles incorporated enhanced wind resistance provisions compared to earlier code editions. Key improvements include strengthened roof-to-wall connections, upgraded door and window performance requirements, and enhanced structural connection details.

The 2018 renovation likely updated mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems to current code requirements while potentially improving envelope performance and energy efficiency. However, structural modifications during renovation may have created discontinuities in load paths requiring engineering verification.

Documentation of as-built conditions and renovation details is essential for engineering assessment. Typical documentation includes architectural drawings, structural plans, mechanical/electrical schematics, and inspection reports from permitting authorities. The American Institute of Architects (AIA) Document G704 provides standard formats for construction documentation.

Wind speed requirements for the Gulf Shores area under IBC 2012 provisions range from 140-150 mph ultimate design wind speeds (3-second gust), depending on risk category and exposure conditions. ASCE 7-10, referenced by IBC 2012, provides wind speed maps and calculation procedures for determining site-specific design pressures.

2.4 What "High Partition" Means in Plain Language

"High partition" refers to interior wall configurations that do not provide continuous structural bracing for roof systems under lateral loading. In sanctuary-type spaces, roof structures must transfer wind forces directly to exterior walls and foundation systems without intermediate support from interior partitions.

This configuration creates specific structural load paths and potential failure modes that engineers evaluate during refuge verification assessments. ASCE 7-22 Chapter 27 provides analytical procedures for determining wind loads on structural elements in buildings with various interior configurations.

Large unobstructed interior volumes may experience wind-induced pressure fluctuations different from those in compartmentalized spaces. These dynamic effects influence structural response and occupant comfort during high-wind events. Wind tunnel testing data, compiled in ASCE 7-22 Chapter 31, provides pressure coefficients for various building configurations and opening arrangements.

2.5 Initial Building Strength: What We Think We Know

Modern construction typically incorporates continuous load paths, adequate connection details, and appropriate materials for design wind loads. However, refuge operations may exceed standard occupancy assumptions, particularly regarding internal pressure loads and dynamic effects during sustained high winds.

Visual indicators of structural adequacy include properly attached roof sheathing, continuous wall framing, adequate foundation connections, and undamaged exterior envelope components. However, connection details and load path continuity require professional engineering verification through drawings review and field inspection.

Building performance during previous storm events provides valuable data for assessment. Post-storm damage assessments, insurance claims, and repair records indicate areas of vulnerability or confirm adequate performance under actual loading conditions.

2.6 What Needs Verification by Baldwin County / Engineer

Structural engineering assessment typically examines load path continuity, connection adequacy, and envelope performance under design wind loads. The International Building Code Section 1609 establishes minimum wind load requirements, while local amendments may impose additional requirements based on regional hazard characteristics.

Key verification areas include:

- Roof System Analysis: Connection details, uplift resistance, and diaphragm continuity per ASCE 7-22 wind load provisions

- Wall Anchorage: Foundation connections, stud-to-plate attachments, and shear wall configurations per IBC Section 2308

- Opening Protection: Door and window anchorage, impact resistance, and pressure rating verification per IBC Section 1609

- Internal Refuge Areas: Identification of safest interior zones during peak wind conditions per FEMA P-361 guidance

- Mechanical Systems: HVAC performance, emergency power requirements, and life safety system functionality per IMC and NFPA standards

County building departments typically require stamped engineering assessments for formal refuge designation. The Alabama State Board of Licensure for Professional Engineers requires structural assessments to be prepared by licensed professional engineers for life safety applications.

Engineering documentation should include structural calculations, annotated drawings showing critical connections, and recommendations for any required improvements. The Structural Engineering Institute (SEI) of ASCE provides guidelines for structural condition assessments and renovation projects.

References

Alabama State Board of Licensure for Professional Engineers and Land Surveyors. (2023). Engineering Practice Guidelines. Montgomery, AL: BELS. Retrieved from https://bels.alabama.gov/engineering/

American Institute of Architects. (2023). AIA Contract Documents. Washington, DC: AIA. Retrieved from https://www.aia.org/contract-documents

American Society of Civil Engineers. (2022). ASCE 7-22: Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures. Reston, VA: ASCE Press.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2021). FEMA P-361: Safe Rooms for Tornadoes and Hurricanes. Washington, DC: FEMA.

International Code Council. (2021). International Building Code. Country Club Hills, IL: ICC.

International Code Council. (2021). International Mechanical Code. Country Club Hills, IL: ICC. Retrieved from https://www.iccsafe.org/products-and-services/i-codes/2021-i-codes/imc/

National Fire Protection Association. (2021). NFPA 101: Life Safety Code. Quincy, MA: NFPA. Retrieved from https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/all-codes-and-standards/list-of-codes-and-standards/detail?code=101

NSF International. (2023). Commercial Kitchen Equipment Standards. Ann Arbor, MI: NSF. Retrieved from https://www.nsf.org/testing-services/by-industry/food-equipment-safety/commercial-food-equipment

3. Understanding the Hazards

3.1 Tornado vs. Hurricane: Why They Are Different

Tornado and hurricane events require fundamentally different structural design approaches due to distinct wind characteristics, duration patterns, and associated hazards. Understanding these differences is crucial for appropriate facility assessment and refuge planning.

Tornadoes generate extreme wind speeds (200-300+ mph) over narrow paths and brief durations, typically lasting minutes. The Enhanced Fujita Scale, used by the National Weather Service, categorizes tornado intensity based on damage indicators, with EF4-EF5 events producing winds exceeding 200 mph. FEMA P-361 establishes design criteria for tornado safe rooms requiring resistance to 250 mph winds and debris impact from 2x4 lumber traveling at 100 mph.

Hurricanes affect large geographic areas with sustained winds and pressure differentials over extended periods. The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale categorizes hurricane intensity from Category 1 (74-95 mph) to Category 5 (157+ mph sustained winds). Hurricane wind fields extend hundreds of miles from the storm center, with tropical storm-force winds (39+ mph) often persisting for 12-24 hours or more.

Structural loading patterns differ significantly between the two hazards. Tornado loading involves extreme peak pressures and rapid pressure changes that can cause building envelope failure and internal pressurization. Hurricane loading involves sustained pressure applications over extended periods that test structural endurance and fatigue resistance rather than peak strength alone.

3.2 Tornado Requirements "Tornado Safe Room"

Emergency management agencies often use familiar terminology when discussing shelter capabilities, and "tornado safe room" has specific meanings in federal guidance documents. However, the requirements for tornado safe rooms far exceed those necessary for hurricane refuge operations in coastal Alabama.

FEMA P-361 defines tornado safe rooms as hardened structures designed to provide "near-absolute protection" from EF5 tornadoes. These facilities require:

- Structural design for 250 mph wind loads with impact resistance

- Continuous reinforced concrete or steel construction

- Impact-rated doors and no windows

- Independent life safety systems

- Professional engineering certification

Such facilities cost $300-600 per square foot for new construction and require extensive modifications to existing buildings. The ICC-500 Standard provides technical requirements for storm shelters, while FEMA maintains a registry of tested and approved shelter products.

3.3 Why Hurricanes Are the Primary Threat Here

Gulf Shores faces hurricane threats as the primary wind hazard requiring evacuation or shelter decisions. National Hurricane Center historical data shows the Alabama coast experiences hurricane-force winds approximately every 7-10 years, with major hurricanes (Category 3+) occurring roughly every 15-20 years.

Hurricane Ivan (2004) produced sustained winds of 105 mph in Baldwin County with gusts to 135 mph. Hurricane Sally (2020) generated sustained winds of 85-100 mph with extensive flooding. These events demonstrate the typical wind speeds and duration patterns that refuge facilities must accommodate.

Tornado events in coastal Alabama are typically associated with tropical systems and produce lower intensity ratings (EF0-EF2) compared to tornado alley regions. The Storm Prediction Center's tornado climatology shows Baldwin County averages less than one tornado per year, with most events producing winds below 150 mph.

Hurricane planning addresses the most statistically likely scenario requiring community refuge operations: sustained winds, extended power outages, and transportation disruptions affecting normal residential occupancy patterns. This focus allows for practical and cost-effective facility improvements rather than extreme hardening measures.

3.4 What Happens in a Major Hurricane (for the people inside)

Hurricane refuge operations typically span 48-72 hours and follow predictable phases that affect facility requirements, operational protocols, and resource consumption patterns. Understanding these phases enables appropriate planning and resource allocation.

Pre-landfall Phase (12-24 hours): Participants arrive with personal belongings, complete registration processes, and settle into assigned areas. Wind speeds gradually increase from normal conditions to tropical storm force (39+ mph). Facility preparation includes securing exterior objects, testing emergency systems, and completing final supply inventories.

Impact Phase (6-12 hours): Hurricane-force winds (74+ mph) make outdoor movement dangerous. Participants remain indoors in designated areas while facility experiences peak structural loading. Power outages commonly occur during this phase, requiring backup lighting and communication systems. Wind noise and building movement may cause anxiety among participants.

Extended Event Phase (24-48 hours): Storm passage involves fluctuating conditions as outer bands and eye wall pass over the facility. Participants experience confinement stress while facility systems operate under emergency conditions. Food service, sanitation, and climate control become increasingly important for maintaining acceptable conditions.

Recovery Phase (12-24 hours): Wind speeds decrease to safe levels for exterior movement and damage assessment. Participants prepare to return home while facility operators assess building condition and coordinate with emergency services. Road clearance and utility restoration determine departure timing.

3.5 What Failure Looks Like (roof loss, debris, water)

Understanding potential failure modes enables realistic risk assessment and targeted mitigation measures. Hurricane building failures typically follow predictable patterns related to wind pressure distribution, structural load paths, and envelope vulnerability.

Roof System Failure: Wind uplift forces concentrate at roof edges and corners where pressure coefficients reach -3.0 or higher per ASCE 7-22. Inadequate connections between roof sheathing, framing, and walls can lead to progressive failure starting at roof perimeters. The Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) research demonstrates that roof edge securement is critical for overall system performance.

Opening Failures: Windows and doors represent the most vulnerable envelope components due to concentrated load applications and dynamic pressure effects. Large opening failures can rapidly increase internal pressure, accelerating structural damage. The American Architectural Manufacturers Association (AAMA) provides performance standards for fenestration products under hurricane conditions.

Water Intrusion: Hurricane rainfall rates commonly exceed 1-2 inches per hour while wind-driven rain penetrates normally weatherproof assemblies. Roof drainage systems may become overwhelmed, causing ponding and additional structural loading. The National Roofing Contractors Association (NRCA) provides guidelines for hurricane-resistant roofing systems and drainage design.

Progressive Collapse: Initial failures in critical structural elements can propagate throughout building systems. Loss of lateral bracing, diaphragm continuity, or load-bearing elements may compromise overall structural stability. ASCE 41 provides analytical procedures for assessing progressive collapse vulnerability.

3.6 Realistic Goal: "Keep the Roof On and Keep People Safe"

Effective hurricane refuge design focuses on maintaining structural envelope integrity and occupant protection during design wind events rather than preventing all possible damage. This approach balances protection levels with practical implementation costs and existing building constraints.

Primary objectives include:

- Load Path Continuity: Ensuring wind forces transfer from roof systems through wall framing to foundation elements without failure or discontinuity

- Envelope Integrity: Maintaining roof covering, wall cladding, and opening protection to prevent water intrusion and internal pressurization

- Safe Areas: Identifying interior spaces with maximum protection from potential debris and structural failure during peak wind conditions

- Life Safety Systems: Maintaining emergency lighting, communication, ventilation, and egress capabilities throughout the event duration

These objectives align with FEMA's "Wind-Resistant Construction" guidelines emphasizing practical improvements that provide significant risk reduction without requiring complete rebuilding. The Federal Alliance for Safe Homes (FLASH) promotes similar approaches through their "Strengthen Your Home" program.

Success metrics focus on maintaining habitability and safety rather than preventing all damage. Post-storm assessments should find minimal water intrusion, no structural damage in occupied areas, and full functionality of life safety systems throughout the event period.

References

American Architectural Manufacturers Association. (2023). AAMA 501.6-18: Voluntary Test Method for Hurricane Impact and Cyclic Wind Pressure Resistance. Schaumburg, IL: AAMA. Retrieved from https://www.aamanet.org/general.asp?sect=3&id=127

American Society of Civil Engineers. (2017). ASCE 41-17: Seismic Evaluation and Retrofit of Existing Buildings. Reston, VA: ASCE Press.

Federal Alliance for Safe Homes. (2023). Strengthen Your Home Program. Tallahassee, FL: FLASH. Retrieved from https://flash.org/strengthen-your-home/

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2019). Wind-Resistant Construction Guidelines. Washington, DC: FEMA. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science

Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety. (2023). Hurricane Research. Richburg, SC: IBHS. Retrieved from https://ibhs.org/risk-research/hurricane/

National Hurricane Center. (2023). Historical Hurricane Database. Miami, FL: NHC. Retrieved from https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/hurdat/

National Roofing Contractors Association. (2023). Hurricane Preparedness Guidelines. Rosemont, IL: NRCA. Retrieved from https://www.nrca.net/resources/public/hurricane-preparedness

Storm Prediction Center. (2023). Tornado Climatology. Norman, OK: SPC. Retrieved from https://www.spc.noaa.gov/climo/

4. Occupancy

Occupancy describes who is present during a refuge activation, how many people can reasonably be inside, and for how long the facility can support them. These questions shape later planning but do not assume any particular model or obligation.

4.1 Possible Occupancy Patterns

Several basic occupancy patterns are possible in a small refuge setting. Examples include:

- Access limited to church members and their households

- A pre-identified list of people who face difficulty evacuating or sheltering safely at home

- Access based on proximity to the church (nearby neighbors)

- First-come, first-served access during a defined activation period

- Lists or criteria developed in conversation with local emergency officials

These patterns are presented as conceptual options only. Any specific approach would be defined locally.

4.2 Example Occupancy Concept for St. Andrew

For a town the size of Gulf Shores and a facility with limited physical capacity, one example occupancy concept focuses on people who are unsafe at home during a storm but do not require hospital care. An example configuration might emphasize:

- Older adults or people with mobility limitations who cannot easily evacuate

- Residents living in manufactured homes or older structures that are not built to current wind-resistance standards

- Individuals without reliable transportation who would otherwise remain in harm’s way

- Medically stable individuals whose health would be at risk in a prolonged outage or high-wind event but who do not need intensive medical treatment

- Small pets accompanying their owners, managed in a simple, contained way

In this example, occupancy planning might include a call list developed in calm conditions and potential use of a church van to bring identified individuals to the building before conditions deteriorate. This is one possible way to think about occupancy in a small facility; other arrangements are also possible.

4.3 Capacity Factors

The number of people who can be inside the building during refuge operations depends on several factors rather than a single number.

Life-Safety Occupancy:

- The International Building Code (IBC) provides baseline occupant loads for assembly spaces, often in the range of 7–15 square feet per person for seated use.

- These calculations are intended for normal gatherings, not for sleeping or prolonged stay.

Refuge and Sleeping Space:

- Emergency shelter planning guidance often uses 40–60 square feet per person as a planning range when people are sleeping on the floor with personal belongings and circulation space.

- Actual planning can consider not only the sanctuary but also halls, classrooms, or other rooms that could be used during activation.

Restrooms and Sanitation:

- Restroom capacity and cleaning effort can become a limiting factor, especially if occupancy continues beyond a single night.

- The International Plumbing Code (IPC) is commonly used as a reference for minimum fixture counts in assembly occupancies.

Ventilation and Temperature Control:

- Ventilation needs increase with the number of people and the length of stay.

- ASHRAE Standard 62.1 provides general guidance on indoor air quality that can inform discussions about generator sizing, fresh air, and comfort.

Practical Oversight:

- The number of people that can be safely and calmly supported also depends on how many volunteers are present to monitor conditions, assist participants, and handle routine issues.

4.4 Duration of Stay

Occupancy planning is tied to how long people may remain in the building during a typical activation. Common planning horizons include:

Up to 24 Hours:

- Used mainly for storm passage or short outages

- Participants may bring their own essential items

- Demands on supplies and building systems remain relatively light

24–48 Hours:

- Requires more deliberate attention to water, snacks or simple food, and restroom cycles

- Temperature control and ventilation become more important to maintain comfort and safety

72 Hours and Beyond:

- Involves careful planning for generator fuel, basic comfort heating or cooling, and simple medical support arrangements

- Volunteer rotation and cleaning routines become more structured

National training materials from organizations such as the American Red Cross use similar time brackets to illustrate how resource needs change as duration increases.

4.5 Volunteer Considerations

Supporting any occupancy model involves work from staff and volunteers. Typical considerations include:

- Moving chairs and furniture to create sleeping areas

- Basic intake or check-in processes when people arrive

- General observation of the space and responding to routine needs

- Fatigue, especially when volunteers also have homes or family members affected by the same storm

National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (NVOAD) and American Red Cross documents describe simple role definitions and shift concepts that can be adapted to small sites.

4.6 Facility Impact

Refuge use concentrates people, equipment, and activity into a short period of time. Examples of facility impacts include:

- Increased wear on restrooms and high-traffic flooring

- Need for post-event cleaning and minor repairs

- Temporary interruption or relocation of routine church activities

Facility management references, including guidance from the International Facility Management Association (IFMA), offer general approaches for planning short-duration, high-intensity use of buildings.

References

American Red Cross. (2023). Shelter Fundamentals; Shelter Simulation Exercise. Retrieved from https://www.redcross.org/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Emergency Sheltering Guidelines. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023). Mass Care/Emergency Assistance Program Guidance. Washington, DC: FEMA.

International Code Council. (2021). International Building Code; International Plumbing Code. Washington, DC: ICC.

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. (2022). ASHRAE Standard 62.1: Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality. Atlanta, GA: ASHRAE.

National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster. (2023). Sheltering and Volunteer Management Resources. Washington, DC: NVOAD.

International Facility Management Association. (2023). Facility Impact Assessment Guidelines. Houston, TX: IFMA.

5. Refuge Planning for Real People

5.1 Who Actually Comes During a Storm?

Storm refuge facilities typically serve diverse demographic groups with varying needs, capabilities, and support requirements. Understanding these population characteristics enables appropriate facility planning, volunteer training, and resource allocation.

5.1.1 Families

Family units with children represent the largest demographic in community refuges, requiring space configurations that accommodate group sleeping, supervised activity areas, and noise management protocols. The Federal Emergency Management Agency's Mass Care Services guidelines recommend family cluster arrangements to maintain social cohesion while providing appropriate supervision.

Children experience stress responses to confinement, unfamiliar environments, and disrupted routines. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network provides guidance on supporting children in emergency shelter environments, emphasizing structured activities, predictable schedules, and adult reassurance.

Space requirements for families include private sleeping areas, secure storage for personal belongings, and designated activity zones. The American Red Cross recommends 40-50 square feet per person for family sleeping areas with additional common space for meals and recreation.

5.1.2 Elderly

Senior participants often present multiple challenges including mobility limitations, chronic medical conditions, sensory impairments, and social isolation issues. The Administration for Community Living provides guidelines for emergency planning for older adults emphasizing environmental modifications and support services.

Physical accessibility requirements include proximity to restroom facilities, minimize stair usage, adequate lighting, and temperature control. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Accessibility Guidelines establish minimum standards for accessible routes, doorway widths, and fixture placement.

Medical considerations include medication management, mobility device accommodation, and potential need for assistance with activities of daily living. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides guidance on medication safety in congregate care settings.

5.1.3 Disabled

Individuals with physical, sensory, or cognitive disabilities require specific accommodations and support protocols. The National Organization on Disability provides emergency preparedness guidelines emphasizing advance planning, assistive technology accommodation, and communication accessibility.

Physical accommodations include wheelchair accessible entrances, adapted restroom facilities, accessible sleeping areas, and clear circulation paths. The International Code Council's ICC A117.1 Standard provides technical requirements for accessible design in various building types.

Communication accommodations may include sign language interpretation, large print materials, and assistive listening devices. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) provides guidelines for emergency communication accessibility during disaster events.

5.1.4 Medically Fragile

Participants requiring powered medical equipment, refrigerated medications, or regular monitoring present significant challenges for community-level refuges. The Department of Health and Human Services maintains registries of special needs populations requiring enhanced support during emergencies.

Power-dependent medical equipment includes oxygen concentrators, CPAP machines, ventilators, and mobility aids. Backup power planning must accommodate these loads while maintaining equipment reliability and safety standards per National Electrical Code (NEC) Article 517 healthcare facility requirements.

Medication storage requires temperature control, security, and proper labeling. The U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention provides guidelines for medication storage in emergency situations, emphasizing cold chain maintenance and contamination prevention.

5.1.5 People Who Are Afraid

Many refuge participants seek primarily emotional security and social support rather than protection from specific physical vulnerabilities. The substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provides guidance on psychological support in emergency shelters emphasizing reassurance, information sharing, and social connection.

Anxiety management techniques include clear communication about facility safety, regular updates on external conditions, and organized group activities. The American Psychological Association provides disaster mental health guidelines for non-professional support personnel.

5.2 What They Bring

Effective refuge operations establish clear guidelines for participant supply responsibilities while maintaining backup resources for unprepared individuals. Supply management affects operational efficiency, volunteer workload, and facility safety.

5.2.1 Medication

Participants should bring minimum 72-hour medication supplies in original containers with clear labeling and dosage instructions. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices provides guidelines for medication management in emergency situations emphasizing patient responsibility and professional oversight.

Controlled substances require special handling protocols to prevent diversion while ensuring participant access. The Drug Enforcement Administration provides guidance on controlled substance security during emergency operations.

Refrigerated medications present storage challenges requiring temperature monitoring and backup power planning. The United States Pharmacopeial Convention establishes storage standards for temperature-sensitive medications in emergency situations.

5.2.2 Phone Chargers

Personal communication devices enable family contact and emergency information access throughout refuge operations. The Federal Communications Commission emphasizes communication resilience as a critical element of emergency preparedness.

Charging infrastructure planning should accommodate diverse device types while managing electrical loads under emergency power conditions. Common charging stations reduce individual outlet requirements while enabling volunteer supervision of electrical usage.

5.2.3 Blankets / Bedding

Personal bedding improves comfort and reduces facility supply requirements while addressing individual preferences and hygiene concerns. The American Red Cross recommends participant-provided bedding as standard practice for community shelter operations.

Backup bedding supplies should accommodate 10-15% of anticipated capacity for unprepared participants or bedding failures. Storage requirements include protection from moisture, insects, and contamination between events.

5.2.4 Pets and Carriers

Pet accommodation significantly affects evacuation decisions and refuge participation rates. The Pet Evacuation and Transportation Standards (PETS) Act requires state and local emergency plans to account for pets and service animals in evacuation planning.

Pet supply requirements include carriers, restraints, food, water, medications, and waste management materials. The American Veterinary Medical Association provides guidelines for pet care in emergency shelter environments.

5.3 What Cannot Come

Clear prohibited item policies protect participant safety, facility security, and operational efficiency. Policy enforcement requires volunteer training and consistent application during high-stress intake periods.

Weapons and Contraband: Firearms, weapons, and illegal substances represent obvious safety hazards requiring clear policies and enforcement procedures. State concealed carry laws may affect weapon policies, requiring legal consultation and coordination with law enforcement.

Hazardous Materials: Flammable liquids, propane tanks, generators, and chemical products present fire and health hazards inappropriate for indoor storage. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) provides guidelines for hazardous material identification and safe storage practices.

Large Appliances: Personal refrigerators, space heaters, and high-power electrical devices may overload facility electrical systems and create safety hazards. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1 Fire Code addresses electrical load management and fire prevention in assembly occupancies.

5.4 Behavior and Stress Management

Extended confinement in crowded conditions creates stress requiring proactive management through environmental design, activity programming, and clear behavioral expectations.

Noise Control: Sound management includes designated quiet hours, activity zone separation, and clear expectations for conversation volume and music. The American Academy of Audiology provides guidelines for noise management in congregate living environments.

Privacy Management: Visual and acoustic privacy improve participant comfort and reduce stress levels. Portable screens, furniture arrangement, and activity scheduling can provide privacy without permanent modifications.

Conflict Resolution: Trained volunteers should be prepared to mediate disputes, enforce behavioral standards, and de-escalate tensions. The American Red Cross provides conflict resolution training specifically designed for shelter operations.

5.5 Privacy, Dignity, and Safety Inside the Building

Maintaining human dignity under emergency conditions requires attention to privacy, personal space, and cultural sensitivities while working within facility constraints and resource limitations.

Sleeping Arrangements: Family clusters, gender-separated areas, and individual space allocation help maintain dignity and reduce stress. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees provides shelter design guidelines emphasizing dignity and cultural appropriateness.

Personal Hygiene: Access to soap, towels, and privacy for personal care maintains health and dignity. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidelines for hygiene maintenance in congregate care settings.

Cultural Sensitivity: Religious practices, dietary restrictions, and cultural customs require accommodation within operational constraints. The National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters provides cultural competency training for disaster relief operations.

References

Administration for Community Living. (2023). Emergency Planning for Older Adults. Washington, DC: ACL. Retrieved from https://acl.gov/programs/aging-and-disability-networks/emergency-preparedness

American Academy of Audiology. (2023). Noise Management Guidelines. Reston, VA: AAA. Retrieved from https://www.audiology.org/

American Psychological Association. (2023). Disaster Mental Health Guidelines. Washington, DC: APA. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/science/about/publications/psychological-science-agenda/2006/03/disaster-relief

American Veterinary Medical Association. (2023). Pet Emergency Planning. Schaumburg, IL: AVMA. Retrieved from https://www.avma.org/resources/pet-owners/emergencycare/pets-and-disasters

Drug Enforcement Administration. (2023). Emergency Controlled Substance Guidelines. Springfield, VA: DEA. Retrieved from https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling

Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2023). Emergency Medication Management. Horsham, PA: ISMP. Retrieved from https://www.ismp.org/resources/emergency-preparedness

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2023). Supporting Children in Emergencies. Los Angeles, CA: NCTSN. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/disasters

National Organization on Disability. (2023). Emergency Preparedness Guidelines. Washington, DC: NOD. Retrieved from https://www.nod.org/disability-advocacy/emergency-preparedness/

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023). Psychological Support in Emergencies. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/dtac

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2023). Emergency Shelter Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/handbooks/eh/

6. Pets (Dedicated Section)

6.1 Why Pets Cannot Be Ignored

Pet accommodation policies significantly influence household evacuation decisions and community participation in refuge operations. Research by the National Science Foundation following Hurricane Katrina demonstrated that pet-related concerns prevented numerous households from evacuating, resulting in preventable casualties and increased rescue requirements.

The Pet Evacuation and Transportation Standards (PETS) Act of 2006 requires state and local emergency plans to include provisions for pets and service animals. This legislation recognizes the critical role of pet accommodation in emergency planning effectiveness and community compliance with evacuation orders.

The American Veterinary Medical Association estimates that 67% of U.S. households own pets, with significant emotional and financial investments in animal welfare. Emergency planning that fails to address pet accommodation may effectively exclude a majority of potential participants from refuge operations.

Community refuge operations benefit from formal pet accommodation policies that balance animal welfare, public health considerations, and operational efficiency. The Federal Emergency Management Agency's Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 101 emphasizes multi-species planning as a component of inclusive emergency management.

6.2 Types of Pets Anticipated

Gulf Coast communities typically maintain diverse pet populations requiring different accommodation strategies and management approaches. The American Pet Products Association's National Pet Owners Survey provides demographic data on regional pet ownership patterns and species distribution.

Domestic Dogs: Dogs represent the most common pet type requiring accommodation, ranging from small companion animals to large working breeds. The American Kennel Club provides breed-specific information relevant to space requirements, exercise needs, and behavioral characteristics under stress conditions.

Size variations significantly affect accommodation planning, with larger breeds requiring proportionally more space and creating greater noise and waste management challenges. Stress responses vary by breed and individual temperament, affecting group dynamics and volunteer management requirements.

Domestic Cats: Felines typically adapt well to carrier-based housing but may experience significant stress in unfamiliar environments. The American Association of Feline Practitioners provides guidelines for cat care during emergency situations emphasizing environmental enrichment and stress reduction.

Litter box management, escape prevention, and noise control represent primary considerations for feline accommodation. Unlike dogs, cats cannot be exercised outdoors during the event, requiring entirely indoor accommodation throughout the refuge period.

Small Caged Animals: Birds, rabbits, guinea pigs, and other small pets often arrive in appropriate carriers but may require specialized care including temperature control, noise reduction, and dietary management. The Association of Avian Veterinarians provides emergency care guidelines for pet birds in stressful environments.

Service Animals: Service animals receive different legal protection under the Americans with Disabilities Act and must be accommodated regardless of other pet policies. The U.S. Department of Justice provides guidance distinguishing service animals from emotional support animals and pets in emergency situations.

6.3 Where Pets Go in the Building

Effective pet accommodation requires designated areas that balance animal welfare, human comfort, and operational efficiency. The American Red Cross Shelter Operations Manual recommends separate pet areas with controlled access and specialized volunteer management.

Primary Pet Areas: Designated spaces should provide adequate ventilation, easy cleaning access, and noise control relative to human sleeping areas. The National Animal Control Association provides guidelines for temporary animal housing in emergency situations emphasizing health, safety, and humane treatment.

Location considerations include proximity to exterior doors for exercise access, separation from food service areas for health code compliance, and acoustical isolation from quiet zones. HVAC systems should provide adequate air exchange to manage odors and allergens.

Exercise and Relief Areas: Outdoor spaces for animal exercise and waste elimination require secure fencing, weather protection, and volunteer supervision. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) provides guidelines for emergency animal exercise areas and waste management protocols.

Weather conditions may prevent outdoor access for extended periods, requiring contingency plans for indoor relief areas and increased cleaning protocols. Artificial turf systems or absorbent materials may provide temporary solutions when outdoor access is impossible.

6.4 Noise Control and Separation

Animal stress responses in unfamiliar environments commonly include increased vocalization, creating management challenges for volunteer staff and comfort issues for human occupants. The American Veterinary Medical Association provides guidance on stress reduction in emergency animal care settings.

Acoustic Management: Sound barriers, white noise systems, and spatial separation help control noise transmission to human sleeping areas. The Acoustical Society of America provides guidelines for noise control in mixed-use facilities.

Accommodation strategies may include relocating particularly vocal animals to isolated areas, providing comfort items to reduce stress, and implementing quiet hours with enhanced supervision. Severe behavioral issues may require removal from the facility to protect other animals and maintain operational effectiveness.

Stress Reduction: Familiar bedding, toys, and owner presence help reduce animal stress and associated behavioral problems. The American Animal Hospital Association provides guidelines for stress recognition and management in emergency situations.

6.5 Cleanliness and Waste

Waste management represents one of the most challenging aspects of pet accommodation, affecting both public health and facility maintenance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidelines for animal waste management in congregate care facilities emphasizing disease prevention and sanitation.

Owner Responsibility: Pet owners should maintain primary responsibility for waste cleanup, feeding, and basic care activities. Clear policies prevent volunteer burnout while maintaining accountability for animal welfare and facility cleanliness.

Supply requirements include waste bags, cleaning materials, disinfectants, and protective equipment for volunteers. The National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians provides guidelines for cleaning and disinfection protocols in animal areas.

Facility Support: Organizations should provide waste disposal containers, cleaning stations, and basic supplies while maintaining clear owner responsibility for daily care activities. Hand washing facilities and sanitizing supplies help prevent disease transmission between animals and humans.

6.6 Rules for Pet Owners

Clear, enforceable policies help maintain order and safety while establishing realistic expectations for pet owners during stressful conditions. The Humane Society of the United States provides model pet policies for emergency shelters emphasizing safety and animal welfare.

Restraint Requirements: Animals must remain contained in carriers or on leashes at all times to prevent injuries, escapes, and conflicts between animals. The American Kennel Club provides guidelines for appropriate restraint equipment and sizing for different dog breeds.

Supervision Standards: Owners must remain with or near their animals throughout the refuge period, with clear protocols for temporary absence due to personal needs. Volunteer pet-sitting services create liability concerns and should generally be avoided.

Health Requirements: Current vaccinations and health certificates help prevent disease transmission, though enforcement during emergency conditions may be impractical. The American Veterinary Medical Association provides guidance on vaccination requirements and health assessments in emergency situations.

6.7 What Supplies the Church Needs to Keep On Hand

Basic pet support supplies help accommodate unprepared owners while maintaining clear boundaries regarding primary responsibility for animal care. The American Red Cross Emergency Pet Care guidelines recommend minimal organizational supply inventory supplemented by owner preparation.

Emergency Containment: A limited number of backup carriers, leashes, and restraint equipment accommodates owners who arrive with inadequate equipment. Carriers should accommodate various animal sizes and include basic ventilation and security features.

Cleaning Supplies: Disinfectants, waste bags, paper towels, and protective equipment enable effective sanitation and volunteer safety. The Association of American Feed Control Officials provides guidelines for cleaning chemical safety around animals.

First Aid Supplies: Basic veterinary first aid supplies may be necessary for minor injuries, though serious medical issues require referral to veterinary professionals. The American Red Cross provides first aid training specifically for animal emergencies.

6.8 "Pet Corner" Layout (Simple, Practical)

Effective pet area design optimizes space utilization while providing adequate circulation, cleaning access, and animal welfare accommodation. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians provides design guidelines for temporary animal housing emphasizing health, safety, and operational efficiency.

Physical Layout: Linear arrangement of carriers along walls maximizes capacity while providing central circulation space. Clear sight lines enable volunteer supervision while allowing animals to see owners and reducing stress levels.

Adequate spacing between carriers prevents animal-to-animal contact while allowing owner access for feeding, cleaning, and comfort activities. The American Animal Hospital Association provides spacing guidelines based on animal size and behavior considerations.

Support Infrastructure: Cleaning stations, waste disposal, and volunteer coordination areas should be integrated into pet area design without interfering with animal accommodation. Clear signage and posted policies help communicate expectations to pet owners and volunteers.

References

American Animal Hospital Association. (2023). Emergency Animal Care Guidelines. Lakewood, CO: AAHA. Retrieved from https://www.aaha.org/professional/resources/emergency_care_guidelines/

American Association of Feline Practitioners. (2023). Feline Stress Guidelines. Hillsborough, NJ: AAFP. Retrieved from https://catvets.com/guidelines/practice-guidelines/feline-stress-guidelines

American Kennel Club. (2023). Dog Care and Training. New York, NY: AKC. Retrieved from https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/

American Pet Products Association. (2023). National Pet Owners Survey. Stamford, CT: APPA. Retrieved from https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp

American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. (2023). Disaster Preparedness. New York, NY: ASPCA. Retrieved from https://www.aspca.org/pet-care/general-pet-care/disaster-preparedness

American Veterinary Medical Association. (2023). Emergency Preparedness Guidelines. Schaumburg, IL: AVMA. Retrieved from https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-health-emergencies

Association of American Feed Control Officials. (2023). Feed Safety Guidelines. Champaign, IL: AAFCO. Retrieved from https://www.aafco.org/consumers/understanding-pet-food/

Association of Avian Veterinarians. (2023). Emergency Bird Care. Teaneck, NJ: AAV. Retrieved from https://www.aav.org/page/EmergencyBirdCare

Association of Shelter Veterinarians. (2023). Temporary Housing Guidelines. Davis, CA: ASV. Retrieved from https://www.sheltervet.org/resources/

Humane Society of the United States. (2023). Emergency Shelter Pet Policies. Washington, DC: HSUS. Retrieved from https://www.humanesociety.org/resources/pets-and-disasters

National Animal Control Association. (2023). Emergency Animal Housing. Olathe, KS: NACA. Retrieved from https://www.nacanet.org/

U.S. Department of Justice. (2023). Service Animals and Emergencies. Washington, DC: DOJ. Retrieved from https://www.ada.gov/resources/service-animals-2010-requirements/

7. Logistics & Operations

7.1 Opening and Closing Protocol

Formal activation and closure protocols ensure consistent, safe operations while providing clear authority structures and decision-making frameworks. The National Incident Management System (NIMS) provides standardized approaches to emergency operations applicable to community-level refuge facilities.

Activation Triggers: Specific weather criteria and official guidance should trigger refuge activation, typically including Hurricane Watch declarations, sustained wind forecasts exceeding 39 mph, or county emergency management recommendations. The National Weather Service provides standardized warning systems and forecast products supporting activation decisions.

Decision Authority: Clear designation of activation authority prevents confusion during rapidly evolving weather situations. Decision-makers should include primary and backup personnel with communication protocols for consultation with county officials when appropriate.

Communication Protocols: Participant notification systems may include phone trees, mass notification systems, social media, and coordination with local media outlets. The Federal Communications Commission's Emergency Alert System provides frameworks for emergency communication coordination.

7.2 When Do Doors Lock?

Intake closure timing balances maximum accommodation with volunteer safety and operational security. The National Hurricane Center provides forecast timing guidance enabling advance planning for dangerous condition onset.

Safety Timing: Door closure should occur before tropical storm-force winds arrive, typically 3-6 hours before forecast onset to allow final preparation activities. Late arrivals create safety risks for volunteers and may compromise facility security during critical preparation periods.

Emergency Access: Post-closure access protocols should accommodate legitimate emergency needs while preventing unauthorized entry. Coordination with law enforcement may be necessary for emergency situations requiring access after closure.

The American Red Cross Shelter Operations Manual recommends formal check-in cutoff times communicated through public information channels and consistently enforced to prevent confusion and maintain operational security.

7.3 Who Is In Charge?

Effective operations require clear leadership hierarchy with defined roles and decision-making authority. The Federal Emergency Management Agency's Incident Command System provides scalable organizational structures applicable to shelter operations.

Shelter Manager: Overall facility coordination including external communication, resource allocation, and major operational decisions. This role typically requires experience in emergency management, facility operations, or organizational leadership.

Functional Leaders: Specialized roles including registration, logistics, food service, health services, and volunteer coordination. The American Red Cross provides training curricula for each functional area emphasizing specific competencies and coordination requirements.

External Coordination: Designated liaison with county emergency management, law enforcement, and utility companies. This role requires communication skills and familiarity with emergency response protocols.

7.4 Who Has Keys?

Access control systems protect facility security while enabling operational flexibility during extended events. The Security Industry Association provides guidelines for access control in institutional facilities during emergency operations.

Key Management: Limited key distribution to essential personnel with tracking systems and clear accountability protocols. Electronic access systems may provide better control and audit capability compared to traditional key systems.

Restricted Areas: Mechanical rooms, electrical panels, and supply storage require controlled access to prevent unauthorized modifications or theft. The National Fire Protection Association provides guidelines for securing critical building systems during emergency operations.

7.5 Volunteer Roles

Comprehensive volunteer organization enables effective operations while preventing individual burnout and maintaining service quality. The Corporation for National and Community Service provides volunteer management guidance for disaster relief organizations.

Registration and Intake: Participant check-in, documentation, and space assignment requiring interpersonal skills and attention to detail. Training should include registration procedures, conflict de-escalation, and emergency protocols.

Logistics and Maintenance: Supply management, facility maintenance, and equipment operation requiring technical skills and physical capability. The International Facility Management Association provides training resources for facility operations and maintenance.

Food Service: Meal preparation, service, and cleanup requiring food safety knowledge and coordination skills. The ServSafe program provides food safety certification appropriate for temporary food service operations.

Health and Safety: Basic first aid, medication management, and health screening requiring medical training and calm demeanor under stress. The American Red Cross provides health services training specifically for shelter operations.

7.6 Communication Systems During a Storm

Reliable communication enables coordination with external agencies, information sharing with participants, and family contact for shelter occupants. The Department of Homeland Security's Communications Sector provides guidelines for emergency communication resilience.

External Communication: Multiple communication pathways including landline phones, cellular systems, two-way radios, and internet connectivity. The Amateur Radio Emergency Service provides backup communication capabilities when commercial systems fail.

Internal Communication: Public address systems, bulletin boards, and organized information meetings help manage participant anxiety and provide updates on external conditions. Clear, regular communication prevents rumors and maintains calm environments.

Participant Communication: Charging stations, Wi-Fi access, and coordination with cellular providers help maintain family contact and access to emergency information. The Federal Communications Commission provides guidance on communication continuity during disasters.

7.7 Power (with or without generator)

Electrical planning affects lighting, communication, life safety systems, and participant comfort throughout refuge operations. The National Electrical Code (NEC) provides installation requirements for emergency and standby power systems.

Grid Power Dependency: Operations assuming normal electrical service require contingency plans for extended outages including battery lighting, manual systems, and communication backup. Power restoration timing varies widely based on storm severity and utility infrastructure damage.

Portable Generator Systems: Temporary power for critical loads including lighting, communication, and refrigeration. The Portable Generator Manufacturers Association provides safety guidelines for generator operation including carbon monoxide prevention and electrical safety.

Permanent Backup Power: Automatic transfer systems and standby generators provide comprehensive power backup but require professional installation and maintenance. NFPA 110 provides installation standards for emergency and standby power systems.

7.8 Water

Water planning must accommodate drinking, cooking, sanitation, and emergency needs while accounting for potential service disruptions and quality issues. The American Water Works Association provides guidance for emergency water planning and storage.

Supply Requirements: Federal Emergency Management Agency guidelines recommend one gallon per person per day for drinking and basic sanitation, with additional allocation for cooking and cleaning activities. Extended operations require proportionally greater storage or resupply capabilities.

Storage Systems: Potable water storage requires food-grade containers, protection from contamination, and rotation to maintain quality. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidance for emergency water storage and treatment.

Backup Sources: Well water, rainwater collection, and commercial suppliers provide alternatives when municipal systems fail. Water quality testing and treatment may be necessary for alternative sources.

7.9 Bathrooms + Sanitation

Sanitation facilities often determine practical capacity limits and significantly affect participant comfort and health during extended operations. The International Plumbing Code provides minimum fixture requirements for various occupancy levels and building types.

Fixture Adequacy: Standard assembly occupancy requirements may be insufficient for extended refuge operations. Temporary fixtures or portable units may supplement existing facilities when necessary.

Maintenance Protocols: Regular cleaning, supply replenishment, and minor repair capability ensure continued functionality throughout refuge operations. The International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials provides maintenance guidelines for temporary and emergency plumbing systems.

Backup Systems: Manual flush capability, portable toilets, and waste storage systems provide alternatives when normal plumbing fails. The United States Environmental Protection Agency provides guidelines for emergency sanitation systems.

7.10 Parking + Traffic Flow

Vehicle accommodation and site circulation affect participant access, emergency response capability, and post-storm departure efficiency. The Institute of Transportation Engineers provides parking and circulation design guidelines for various facility types.

Capacity Planning: Vehicle storage requirements depend on household size, arrival patterns, and duration expectations. Emergency access lanes must remain clear for fire, medical, and law enforcement response throughout the event.

Security Considerations: Vehicle security, access control, and damage prevention require parking area management and potential volunteer supervision. Clear policies regarding vehicle access and responsibility help prevent conflicts.

7.11 Sleeping Layout and Capacity

Space allocation significantly affects participant comfort, operational efficiency, and facility capacity calculations. The American Red Cross provides detailed guidance on shelter layout and capacity planning based on operational experience.

Space Standards: Recommended allocations include 40-60 square feet per person for sleeping areas plus additional space for circulation, storage, and common areas. Family grouping and privacy considerations may increase space requirements.

Layout Design: Advance layout planning prevents improvisation under stress while accommodating different family sizes and special needs. Clear circulation paths, emergency egress, and volunteer supervision areas should be integrated into layout designs.

7.12 Food + Refrigeration + Warmth

Food service operations range from simple participant self-service to comprehensive meal preparation requiring different resources, volunteer skills, and regulatory compliance. Local health departments provide temporary food service guidelines and permitting requirements.

Service Models: Participant-provided meals minimize organizational burden but require adequate refrigeration and reheating capability. Full meal service requires commercial kitchen capacity, trained volunteers, and food safety protocols.

Refrigeration Requirements: Medication storage, food safety, and participant comfort may require reliable refrigeration throughout extended operations. Backup power planning must accommodate refrigeration loads and temperature monitoring.

7.13 Medical Emergencies

Medical emergency response requires advance planning, trained personnel, and coordination protocols with professional emergency services. The American Red Cross provides health services training specifically designed for shelter operations.

First Aid Capability: Basic first aid training and supplies enable response to minor injuries and common medical issues. However, serious medical emergencies require professional emergency services and hospital transport.

Medication Management: Participant medication needs may require basic assistance, storage support, and emergency protocols for critical medications. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices provides guidelines for medication management in emergency settings.

7.14 Security (Non-police)

Basic security measures protect participants and property while maintaining calm environments conducive to rest and recovery. The Security Industry Association provides guidelines for security planning in institutional facilities.

Access Control: Perimeter security, entrance monitoring, and visitor control help maintain safe environments and prevent unauthorized access. Clear policies regarding visitors and deliveries help manage security risks.

Conflict Management: Trained volunteers should be prepared to de-escalate conflicts, enforce facility rules, and coordinate with law enforcement when necessary. The American Red Cross provides conflict resolution training for shelter operations.

7.15 Cleaning After the Event

Post-event cleanup and damage assessment enable facility restoration and preparation for future operations. Documentation of lessons learned and improvement opportunities supports continuous improvement of refuge capabilities.

Cleaning Protocols: Comprehensive sanitization, damage assessment, and facility restoration may require professional cleaning services depending on usage intensity and potential contamination. The Institute of Inspection Cleaning and Restoration Certification provides guidelines for post-disaster facility cleanup.

After Action Review: Systematic evaluation of operations, challenges, and successes enables improvement planning and volunteer development. The Federal Emergency Management Agency's Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program provides frameworks for emergency exercise evaluation applicable to actual operations.

References

American Water Works Association. (2023). Emergency Water Guidelines. Denver, CO: AWWA. Retrieved from https://www.awwa.org/Resources-Tools/Resource-Topics/Emergency-Preparedness

Federal Communications Commission. (2023). Emergency Communications. Washington, DC: FCC. Retrieved from https://www.fcc.gov/general/emergency-alert-system-eas

Institute of Transportation Engineers. (2023). Parking Generation Manual. Washington, DC: ITE. Retrieved from https://www.ite.org/technical-resources/topics/parking/

International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials. (2023). Emergency Plumbing Guidelines. Ontario, CA: IAPMO. Retrieved from https://www.iapmo.org/

National Fire Protection Association. (2023). NFPA 110: Emergency and Standby Power Systems. Quincy, MA: NFPA. Retrieved from https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/all-codes-and-standards/list-of-codes-and-standards/detail?code=110

Portable Generator Manufacturers Association. (2023). Generator Safety Guidelines. Arlington Heights, IL: PGMA. Retrieved from https://www.pgmaonline.com/safety

Security Industry Association. (2023). Security Planning Guidelines. Silver Spring, MD: SIA. Retrieved from https://www.securityindustry.org/

ServSafe. (2023). Food Safety Certification. Chicago, IL: National Restaurant Association. Retrieved from https://www.servsafe.com/

8. Supplies & Equipment

8.1 Minimum Equipment List

Essential equipment ensures basic operational capability even when participants arrive unprepared or facility systems experience failures. The Federal Emergency Management Agency's Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 101 provides equipment planning frameworks for emergency operations at various scales.

8.1.1 Flashlights